Going viral in social media - networks & intercepted misinformation

Posted on 28 August 2014

Going viral in social media - networks & intercepted misinformation

By Luke Sloan, Matthew Williams and Pete Burnap of the COSMOS Project, Cardiff University.

By Luke Sloan, Matthew Williams and Pete Burnap of the COSMOS Project, Cardiff University.

This article is part of our series: a day in the software life, in which we ask researchers from all disciplines to discuss the tools that make their research possible.

It’s any organisations’ worst nightmare. Be it a faulty product or a food scare, the impact of rumour can be significant both for businesses and regulators. This has always been the case, but the advent of social media and proliferation of platforms such as Twitter have enabled faster and more extensive flows of information, thus greatly increasing the speed at which misinformation can spread.

So what happens when a food scare such as the 2013 horse meat scandal comes to the surface? How should industry stakeholders and regulators act? Indeed, is it even possible for them to respond to inaccuracies and properly address public concerns by communicating accurate information through social media?

It is essential to understand how information propagates through these networks in order to address public concerns. Twitter is an example of a very powerful information dissemination network where actors with substantial network capital, such as having a lot of followers or being seen by other users as an authority, can state an opinion which can quickly go viral.

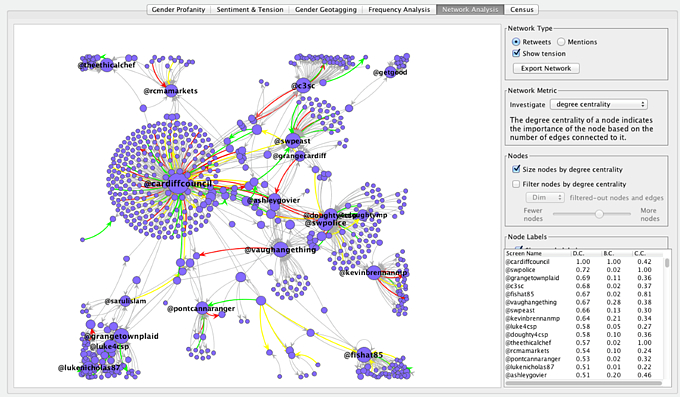

For major food scares such as the recent horsemeat scandal, such powerful agents can set the tone and wield great influence over the public even if they are misinformed or are in fact promoting a disruptive agenda. In these cases, it is essential that consumer interests are put first, and that the relevant organisation counters the misinformation with clear and accurate content. This can be a challenge - the structure of the network and its key actors differ for every event so preparation is difficult, hence the need for real-time monitoring of developing crises on Twitter through the visualisation of networks.

Producers of content with high levels of network capital are always in the centre of the graph. Once identified they can be engaged with directly on Twitter using the @ function and their followers will be able to watch the conversation unfold, which allows the flow of misinformation to be controlled.

Just as important as the producers are the bridges – those social media users who link virtual communities together and retweet or comment upon content. These users are moderators between sub-groups and facilitate the spread of information, good or bad. The situation can be viewed through the lens of epidemiology where a rumour is a virus which originates with one person, or bridge, who then spreads it through the rest of the network.

If we revisit the infection metaphor, everyone connected to that person has a chance of becoming ‘infected’ with and passing on the bad information, or rather, reading it on their Twitter feed and then choosing to retweet it. Not everyone will do so, of course, as some of us have natural immunity to certain strains of bad information. That is to say, our interest is not peaked by certain types of issues, or we will be infected but not pass it on as the information flow stops with us and no further tweeting or bridging occurs. Should the misinformation originate with someone on the edge of the network then the likelihood of an epidemic is also smaller than for an origin at the centre.

Yet the virus analogy is misleading because it carries negative connotations – for the organisation trying to communicate accurate information, a highly infectious and virulent tweet is precisely what is needed. As with any outbreak of disease, however, it is critical that any problems are caught early. Countering the threat requires real time monitoring of accurate and reliable data that is constantly being refreshed and updated as the situation progresses.

An example of a Twitter network based around social issues in Cardiff.

A recent study of Twitter information flows identified social, content and temporal features were key in predicting whether a tweet was statistically likely to go viral. One recent COSMOS study, published in the international peer reviewed journal Social Network Analysis and Mining, showed an increase in retweet likelihood of around 75% when tweets contained a hashtag and a URL.

This suggests that people follow an event using the hashtag to identify relevant tweets, and propagate URLs due to the inclusion of supporting evidence or commentary that substantiates or refutes claims and rumour. Information also spreads more when there was more news coverage related to the issue, suggesting that the media has the power to stir up a frenzy following events of significant public interest. Tweets tended to go viral when a tweeter had a large number of followers, or when a tweet was retweeted rapidly after being posted. The quicker a tweet got its first five retweets, the more likely it was to become a large information flow.

From a risk governance perspective it is clear that the propagation of information on Twitter tends to happen instantly and in bursts, and requires rapid interjection from an authoritative Twitter figurehead - once again, someone with a large number of followers. Providing evidence for or against rumour in the tweet is also essential and significantly increases the likelihood of virility. Food for thought maybe?