Attachment and Turing: the un-disposal of ubiquitous AI

Posted on 11 April 2012

Attachment and Turing: the un-disposal of ubiquitous AI

By Malte Ressin, research student at the University of West London.

By Malte Ressin, research student at the University of West London.

There is a Garfield comic whose three panels tell a story that goes something like this:

John [optimistic]: Wouldn't it be great if everyday items could talk? The sink would say 'Good morning John', and the mirror would say 'You're looking splendid, John'.

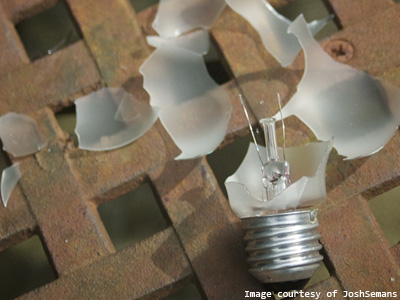

Garfield [cynical]: I wouldn't like that. A blown light bulb would be like a death in the family.

Artificial intelligence and ubiquitous computing, should they ever arrive, might be just what John had in mind. Not only computers and smartphones, but also cars, refrigerators, and - why not - even light bulbs and deposit bottles might eventually wish us a good morning and converse with us in natural language. Regarding Garfield's grim prediction, there could be backups. Indeed, the arrival of artificial intelligence has been described as the singularity after which all bets are off, any prediction of the future will become moot, as nobody is able to predict what will happen once smart machines design ever smarter machines.

I agree that predictions about future developments will become difficult in the face of artificial intelligence. This is not due to the progression of superhuman thinking along the slope of Moore's Law, but rather it is a result of our own limited understanding of a construct that psychologists call intelligence. What is intelligence? Intelligence is what the IQ test measures, anyone?

I wonder if the Turing test (where an automaton is deemed intelligent if it exhibits responses indistinguishable from human responses) is actually the road to fallacy. Its elegance is captivating and its philosophical argument is impeccable, but the Turing test is really just a measure of human-ness - not intelligence. The elicitation of emotional responses, and the subsequent creation of emotional attachment, should not be confused with intelligence.

To illustrate my point, just take voice recognition and natural language processing in smartphones to its logical sequel: how am I ever going to dispose of a device that is so intelligent that I am unable to distinguish its responses from a human being? Will a company that creates Turing-test-passing devices going be as unsuccessful as a car company that manufactures long-lasting cars? It's not like forming an attachment to inanimate objects is difficult: I already find it hard to apply morally bad choices in Knights of the old Republic or Mass Effect.

Maybe the danger lies in familiarity, with ubiquitous intelligent technology conditioning us to have a low level of empathy. What would we become if we get used to disposing of our intelligent, but blown, light bulbs?