As explained in a previous post, 150 Expressions of Interest for the first round of the Research Software Maintenance Fund (RSMF) were invited to submit a full application, and 143 went on to do so.

In this blog, we share more detail on how the submitted full applications were assessed, provide some statistics about the applications and remark on some of the things that we have learned from the process.

Panel composition

We recruited 45 panel members and 8 panel chairs to review the applications. Of these, 8 were based in Europe, with the rest based in the UK. They were based in 37 different organisations, with 9 based in non-university research organisations, and 4 in non-profit organisations or independent contractors.

The recruitment process drew on three pools of people: directly invited experts (based on their specific expertise and experience), an open call for reviewers (who were then screened and invited to panels based on their expertise), and an invitation to unsuccessful applicants at the RSMF EoI stage. Our aim was to get a pool of people who could cover the wide diversity of application areas and applicants, based on the EoIs that were being taken forward. This allowed us to complete recruitment before the full application deadline. Panels also had a small number of early career observers, recruited through an open call, with the intention of giving people experience of the panel process. Panel members were paid fees at the standard UKRI rates and panel observers were paid the equivalent of half a day.

There were two unexpected challenges to the recruitment process: due to the sharing of some personal information with reviewers, the legal department at the University of Edinburgh (the lead organisations for the Software Sustainability Institute) would only allow us to recruit reviewers from the United Kingdom, European Union and New Zealand; and we had three potential reviewers pull out early in the process due to concerns about whether this would affect the status of their skilled worker visas. This latter issue might benefit from further investigation: in theory, people on UK skilled worker visas are allowed to work up to 20 hours per week on other “highly skilled” jobs and, in the case of people based in universities and research organisations, taking part in peer review is often a part of the job description (more often for researchers than research technical professionals). It also isn't clear if the reviewer waiving their fees would be sufficient, as voluntary work can only be done for registered charities, voluntary organisations or statuary bodies; though the University of Edinburgh is a registered charity, potential reviewers aren’t willing to take the risk.

There were four panels, each with two panel chairs and between 10-11 panel members. Each panel member reviewed 9-11 applications, with panel chairs contributing some additional reviewers and being asked to have a general overview of all applications in their panel. There were two panels assessing 69 large award applications (one for the physical sciences / engineering / environmental sciences / computer science / mathematics applications and one for the life sciences / arts and humanities / social sciences applications) and two panels assessing 74 small award applications (one for the physical sciences / engineering / computer sciences / mathematics applications and one for the life sciences / environmental sciences applications). There were research software engineers represented on each panel, with the large award panels also having members with community engagement expertise and industry experience.

Assessment criteria

Four criteria were used to assess the full applications, with an equal weighting given to each:

Impact: the impact this work, if funded, will have on the tool/software (e.g. in terms of improved maintenance or ease of adoption) and the impact the improved tool/software is likely to have on the research area / community

Value: the wider value added by the proposed work, beyond the direct impact on the software and its users. This might include advancement in good practices; the benefits provided to the wider research / research software ecosystem and improving the diversity of users and contributors.

Feasibility: evidence that the funded work is likely to deliver the objectives and benefits. This includes whether the plan of work realistic, the activities sufficiently resourced and in appropriate order, the mechanisms to track the progress of work, and what considerations for future sustainability of the tool/software had been made.

Quality: evidence that the quality of processes and procedures in place for maintaining and developing software are of a high level, that the community around the tool/software is being properly engaged and managed, and that the team have the capability to deliver the proposed work.

Three reviewers were assigned to each application, and asked to grade each application based on the following scoring system taken from UKRI:

Exceptional (6): the application is outstanding. It addresses all the assessment criteria and meets them to an exceptional level. This application should be highly prioritised for funding.

Excellent (5): the application is very high quality. It addresses most of the assessment criteria and meets them to an excellent level. There are very minor weaknesses. This application should be prioritised for funding.

Very good (4): the application demonstrates considerable quality. It meets most of the assessment criteria to a high level. There are minor weaknesses. This application should be funded.

Good (3): the application is of good quality. It meets most of the assessment criteria to an acceptable level, but not across all aspects of the proposed activities. There are weaknesses. This application could be funded.

Weak (2): the application is not sufficiently competitive. It meets some of the assessment criteria to an adequate level. There are, however, significant weaknesses. This application should not be funded.

Poor (1): the application is flawed or of unsuitable quality for funding. It does not meet the assessment criteria to an adequate level. This application must not be funded.

Originally, we had advertised that we would assess against a four-category scale. We decided to change to using the six-category framework, to give more range at the top end of the scale, as we expected lots of high-quality applications. The mapping between the old and new scales is: Excellent > Exceptional (6) & Excellent (5), Good > Very Good (4), Adequate > Good (3), Unsatisfactory > Weak (2) & Poor (1).

Pre-scores and comments were used as the basis for panel discussions before a panel score was agreed.

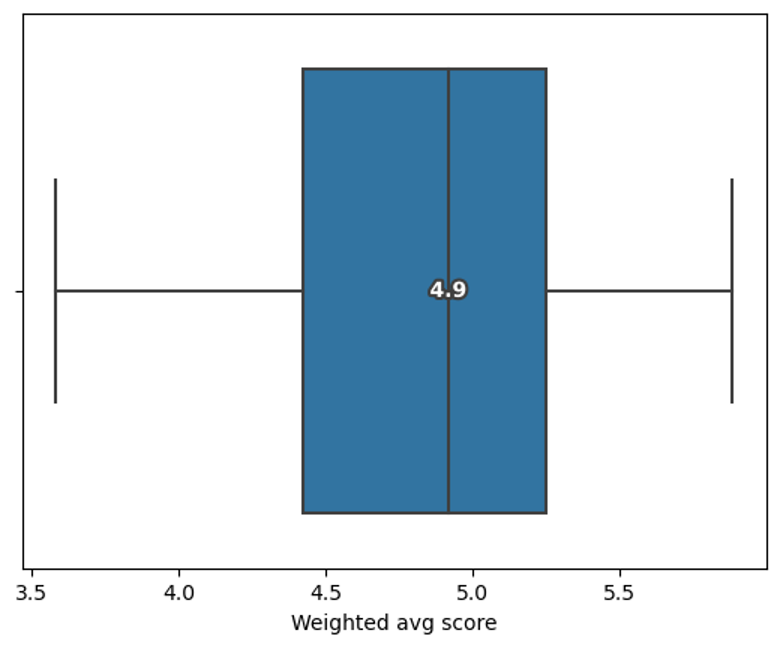

The boxplot above shows the distribution of the pre-scores for the 143 full applications submitted. The mean value of application pre-scores was 4.83 and the median value was 4.92. All applications scored in the range that would be considered fundable if budget allowed, and 61 had pre-scores of 5 or higher.

Panel discussion focussed on applications where there was a large variance in reviewer pre-scores, and where applications had had high pre-scores from all reviewers. After panel discussion, six applications moved up a grade and three applications moved down a grade. This left 11 proposals scored by the panel at a grade of 3, 68 proposals at a grade of 4, and 64 proposals at a grade of 5. All proposals with an agreed panel score of 5 or above were then ranked, with the highest-ranking applications taken forward to a tensioning meeting between the panel chairs for the two large award panels and the two small awards panels, to create a list of recommendations for funding.

Recommendations for funding

In total, the four-ranked large award applications and nine small award applications (the eight top-ranked, plus the 11th ranked) were recommended for funding. The reason for choosing the 11th ranked small award application over the two above it was primarily because of budget limitations (it was substantially smaller than the other two, enabling it to fit within the budget allocated for this round) and partly to give a balanced portfolio across different disciplinary areas. In total, the amount of funding requested was £2,999,024.50.

The 13 applications covered research areas from all seven UK research councils, and involved software written in C, C++, Fortran, JavaScript, PHP, Python and R. The earliest released software was from 1995 and the most recent released was from 2022. They came from 10 lead organisations and included 26 organisations as part of their team or project partners, of which 11 were from outside the UK. Three are led by Research Technical Professionals, and three are led by women.

Lessons learned and next steps

One of the objectives of the Research Software Maintenance Fund was to gather evidence and provide recommendations to help understand how to better manage similar calls. Some of the things we learned around recruitment were unexpected, and many were due to the large number of applications.

The recruitment of panel members raised new concerns around the ability to recruit a diverse group of reviewers, with worries about visa issues and data protection concerns limiting the location or origin of reviewers. We strongly believe that reviewers should be compensated for their time, to ensure that the broadest range of expertise can be accessed. However, if this causes issues with visas, this could cause an imbalance – particularly as Research Technical Professionals and early career researchers are more likely to be on precarious contracts or waiting to be granted indefinite leave to remain. It is also the case that recruiting a pool of 50 reviewers is not sustainable if the call was to run on a more regular basis alongside other calls with similar scope. This is mostly down to the overwhelming demand for the fund but is something to be aware of. It also introduces administrative challenges as each reviewer needs to be set up as a supplier to the University of Edinburgh to enable payment of fees, which can take time if the reviewer has not previously registered for a Unique Taxpayer Reference. The recently funded dRTP Network+ projects are experimenting with a shared reviewer bank, which might be a way of helping manage this.

With so many reviewers and reviews, there were differences in scoring ranges. A key mitigation is to compare reviewers’ scores with their comments. Currently this is the role of the panel chairs, but this is a place where some automation or tooling to analyse the comments might help highlight any that need further discussion.

In the end, due to the budget limitations, we were only able to recommend funding of 13 applications from 143 submissions. Ultimately, this means that a lot of time will have gone in from applicants, panels, and the RSMF team—perhaps more than can be justified for the number of awards. For this first round, we wanted to be deliberately broad, to understand the types of activity that the community felt needed funding. For future rounds, we will consider different ways to limit the number of full applications to ensure that we are able to fund a larger proportion of the submitted applications.

Potential ways of doing this might include:

Limiting the scope of what is allowed to be submitted, e.g. requiring a certain number of users, or a certain amount of previous support / funding, or focusing on a particular type of activity such as community engagement or reducing an issue backlog

Reducing the maximum budget, to enable a larger number of awards to be made with the same amount of funds, thereby restricting applicants to more discrete, short-term activities

Concentrating on areas which have traditionally been underrepresented in funding opportunities

Reducing the number of EoIs submitted, e.g. by limiting the number per applicant or lead organisation

Reducing the number of EoIs going forward to full application, looking to achieve a balance of fairness and effort to implement. Methods might include wider use of lotteries, applicant peer review (as trialled by the UKRI Metascience Early Career Fellowships) or implementing a portfolio approach based on lead organisation or disciplinary area

Finally, despite encouraging RTPs to apply as leads, most of the applications recommended for funding were led by academic researchers. In one of the three awards led by an RTP in practice, the application had to be submitted with an academic as the lead (but with no resources requested, and with a clear indication in the application that the real lead was the RTP). This exemplifies the difficulties and inequalities that can be faced by RTPs in leading applications.

We will be reviewing the way we run the RSMF for Round 2, and seeking advice on any proposed changes, to see if we can create a more efficient process. We will announce further details on Round 2 in December 2025.

A future blog post will look at an analysis of the whole of the RSMF Round 1 from start to finish, as well as going into more detail of some of the mitigations we might recommend improving the ability to run similar calls in the future.