| This blog is part of the Collaborations Workshop 2025 Speed Blog Series. Join in and have a go at speed blogging at Collaborations Workshop 2026. |

Research software is an increasingly important element of research across almost all domains. Its development, maintenance, and adaptation to new use cases require a blend of subject expertise, programming skills, and socio-technical capabilities that are often spread across teams. To support the rapidly growing need for software development for research processes, the role of the “Research Software Engineer” (RSE) has emerged and developed over the last decade, professionalising previously informal positions often held by postdocs. However, how we effectively recognise, reward, and support all those who make contributions to research software is an ongoing discussion and challenge. We cannot cover all aspects in this post, but we will try to describe key approaches and some of the issues surrounding them.

What do we mean by recognition and reward?

The fundamental question to answer is: what are we recognising and why? Codebase level contributions can include infrastructure, testing, sustainability, maintainability, reproducibility, and mentoring. State of the art contributions can include reusable tools, practices, or community standards. Some of these can be measured quantitatively with metrics, some qualitatively, and some narratively. We briefly discuss available options below.

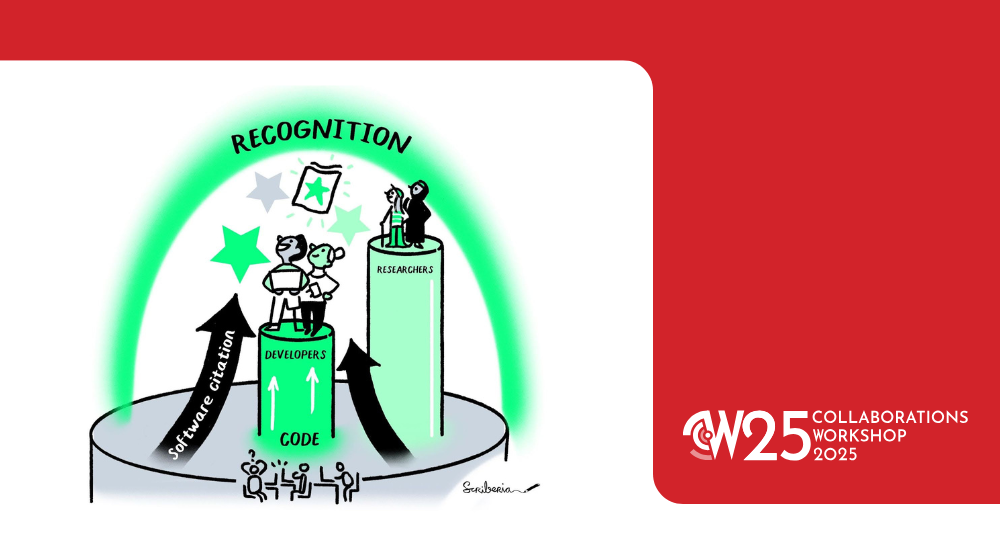

Recognition that a contribution has been made – whether to the specific codebase, the project, the state of the art, a process, or a community – allows the recipient to feel that their contribution has been appreciated by a community. Recognition is about the acknowledgement of the skills, effort, and outcomes achieved by people. It can be as simple as a “thank you”, but may also extend to feedback that enhances the contributor’s reputation within a community. Sites such as StackOverflow rely on such approaches to maintain contributions. Citations for software are one way to recognise contributions, but there are so many more possibilities. Recognition of contributions can also extend into tangible rewards, e.g., monetary rewards, or career opportunities that translate into long-term benefits and ensure that people can continue to contribute and flourish. Reward and recognition are thus not distinct categories – a good reputation can improve career prospects.

There are at least two kinds of rewards. One-off displays, for example, bonuses, gifts, and awards. Then there's the ultimately more important rewards which manifest in terms of someone’s long-term career - like a title change, promotion, the ability to shift between institutions or even move into or out of academia, industry, or public services, based on the strength of contributions to research software projects. This latter form of reward is perhaps less obvious to early career software engineers, but is important down the line. It can affect eligibility for hiring panels, promotion boards, or even funding bodies. In other words, reward and recognition enable movement and credibility. This type of reward requires recognising contributions in a way that is credibly shareable with others.

What matters can vary significantly by contributor. It will also depend on their desired career path and current stage, and so is likely to vary over time. For those within an academic environment who eventually aim to become professors or permanent researchers, citations, visibility, and reputation within their field, leading to recognition within university promotion schemes, will be valued. Within an industry context, being able to show the impact your work has had on the company’s performance will typically lead to salary increases, one-off bonus payments, or new career opportunities.

The hybrid nature of many research technical roles means some research software contributors find themselves on a research career track, while others are considered technical professionals. Each of these comes with its own notions of reward and recognition, which drive promotion criteria, career development, and salary raises. A technical-track person will be less inclined to chase academic publication metrics, since these are not prioritised when evaluating individual performance. Further, the domain in which a person finds themselves working will also play a part. In Bioinformatics, for example, having even a minor role in a Bioinformatics Resource Center (BRC) can ensure authorship credit on the annual release paper (with dozens of others), garnering many citations for proportionally little effort compared to a publication covering a novel software tool. This inconsistency could skew reward incentives for a person on a research track. It also disincentivises academics from contributing to existing software, since this is unlikely to lead long term to the types of recognition required to advance in their careers.

Groups or teams also need collective recognition as they seek to establish or maintain their reputation. Being recognised for their work leads to them being more sought out as trusted collaborators, potentially resulting in ongoing funding for the team and increased sustainability for their work. Having more users of a piece of software both enhances and is driven by the reputation of the developers and may be leveraged to secure funding, or to translate users into contributors. The importance of such recognition to a team will depend on its institutional context, but all teams need to be able to justify their continued existence along these lines.

Critically, the academic structures for reward and recognition lead to particular challenges for maintaining research software. Instead, novel development is heavily weighted in many cases. Despite acknowledging that it is important that existing software tools are maintained, our current global system does not sufficiently reward this work, causing maintainer burnout, unreliable tools, and the reinvention of the wheel over and over. We need a better system for aligning incentives, career development and satisfaction, and the actual needs of the research community.

How do we evaluate contributions? Qualitative vs quantitative

There are numerous different approaches to measuring and evaluating the quality and utility of people's contributions to research software, encompassing a range of factors, both countable (quantitative) and more nebulous (qualitative). Broadly, historically speaking, these evaluation techniques have focused on the more quantitative side of metrics.

Attempts at improving documentation and evaluation of software have tapped into various pre-existing “traditional” metrics. In academia, publications and citations dominate, and projects utilise both software papers and DOIs for code. Efforts such as the Citation File Format project aim to make it easier for researchers to acknowledge the code they utilise, but still emphasise citation number as a key value metric for software. In the general software development realm, community impact is demonstrated through metrics such as contributions on third-party platforms (GitHub, StackOverflow, etc.) or being recognised as a core maintainer for a software application, tool, or library. Such quantitative metrics, whether GitHub stars, citation numbers, lines of code, downloads, etc. are alluring because of the ease of collection and ready translation across projects and domains. However, the homogeneity of these metrics means they can only tell a superficial story. For example, are people starring a particular repository because they're actively using the tool, because they want to come back and look at it later, or because they plan to include it in a list of resources for other people? If someone contributes 1,000s of lines of code to a project, does that automatically make them a better programmer than someone who contributes 100s?

An overzealous focus on readily quantifiable metrics can only ever tell a fraction of the story of a tool or piece of software, and its utility and impact. Likewise, these metrics are often in danger of being gamed, which can introduce skew into evaluations based upon them. One alternative, a narrative approach to describing contributions and software use, delivers much more information about real impact, but places a greater burden on both the author and the reader. It can be hard from a qualitative perspective to capture the breadth and scale of reach of online research outputs. It also presents a barrier to those who experience challenges with reading/writing or are not working in their native language.

Ideally, we need a combination of the two types of metrics. We can incorporate recognised metrics, each of which tells one part of a story, into a broader narrative as evidence behind a more complete story. Funders could easily implement this approach for future grant applications, although this should also be accompanied by corresponding guidance for panel members in how to interpret this new combined narrative approach to evidence.

Conclusion

Recognising and rewarding software contributions can take as many forms as there are people writing code, reviewing pull requests, leading project meetings, researching users, creating documentation, and delivering training. Individuals are likely to all want and need different types of reward and recognition depending on their career stage, ambitions, personal motivations, and job description. However, the consensus in our speed blog is that the current approach, which is still largely focused on citations, downloads, or other quantitative metrics, when it is not focused on the impact factor of the journal, does not capture the full picture.

Efforts such as the Citation File Format, All Contributors bot, the Software Authorship and Contribution Task Force, and the Journal of Open Source Software all seek to address parts of the puzzle of recognition, but none are expected to comprehensively cover the full spectrum of individual needs for recognition. There is also a major challenge in developing wider acceptance of new approaches to recognition and reward in the context of research software, especially in communities that have long-established structures that are fundamental to the way that they manage career progression.

It's unlikely to find a 'one-size-fits-all' solution that adequately captures the complexities and reality of software projects, but we propose that a mixed methods approach to assessment, combining quantitative metrics alongside more in-depth user and impact stories, should be pursued as a path forward.

If you're interested in advocating for improved recognition and reward for research technical professionals:

- Join communities and projects that are working on these problems, in addition to those referenced above: STEP-UP, The Turing Way, RSE Society, SSI itself.

- Think about how you and your institution can recognise and reward people who contribute to research software in ways that they can meaningfully build on.

- Look for opportunities to highlight the value of the work that technical professionals do, whether that's external awards (like HiddenREF or RSE Society Awards), institutional kudos (for example, staff recognition or open science awards), blog posts, or even a festival.

Authors (equal attribution) | |

| Will Haese-Hill | University of Glasgow, william.haese-hill@glasgow.ac.uk, 0000-0002-1393-0966, @haessar.bsky.social, Github |

| Tamora James | University of Sheffield, t.d.james@sheffield.ac.uk, 0000-0003-1363-4742 |

| Stephan Druskat | German Aerospace Center (DLR), stephan.druskat@dlr.de, 0000-0003-4925-7248 |

| Michael Sparks | University of Manchester, michael.sparks@manchester.ac.uk , 0009-0001-3059-0000 |

| Jonathan Cooper | UCL Advanced Research Computing Centre, j.p.cooper@ucl.ac.uk, 0000-0001-6009-3542, LinkedIn |

| Jeremy Cohen | Imperial College London, jeremy.cohen@imperial.ac.uk, 0000-0003-4312-2537 |

| Jack Atkinson | University of Cambridge, jwa34@cam.ac.uk, 0000-0001-5001-4812, @jatkinson1000, Mastodon |

| Arielle Bennett | The Alan Turing Institute, ariellebennettlovell@gmail.com, 0000-0002-0154-2982, @arielleb.bsky.social |

| Adrian D’Alessandro | Imperial College London, a.dalessandro@imperial.ac.uk, 0009-0002-9503-5777 |