| This blog is part of the Collaborations Workshop 2025 Speed Blog Series. Join in and have a go at speed blogging at Collaborations Workshop 2026. |

Introduction

The use of GenAI tools has become one of the most polarising topics in technology today, and the Research Software Engineering (RSE) community is no exception. In many RSE teams, there's a notable divide: some embrace them enthusiastically, while others maintain their distance, viewing LLM-based AI as overhyped, unreliable, unethical, or fundamentally threatening to their profession. This reluctance and scepticism may be particularly pronounced among senior developers and those with extensive experience. While many RSEs have experimented with basic tools like GitHub Copilot, relatively few have fully integrated advanced AI coding assistants into their daily workflows, potentially missing out on significant productivity improvements that early adopters consistently report.

At the recent Collaborations Workshop 2025, our discussion group tackled various concerns about the use of AI tools (generative AI, large language models, and similar AI tools) in research software development. Throughout this text, 'AI' refers to these generative AI technologies. Two major concerns were central in current RSE experiences: first is the concern about whether AI will make RSEs redundant. Second is the question of reliability and dependency: when using AI tools, how do we know when we're being "driven into a river"? This metaphor, inspired by over-reliance on GPS navigation [26], captures the risk of becoming too dependent on AI assistance such that we lose the ability to recognise when it is leading us astray.

What emerged was a clear message: while fears about AI are valid, choosing not to engage isn't a viable option. Those who don't engage with AI tools may find themselves at a disadvantage, while those who master them may enhance their unique value as RSEs. Training in AI literacy, using existing best development practices, development of critical evaluation skills, as well as establishment of community standards are needed to harness AI's power while capitalising on the domain and research expertise that defines excellent research software engineering.

The AI Dilemma: Promise and Peril

The Concerns Are Real

The anxiety around AI isn't unfounded. RSEs are raising legitimate concerns about:

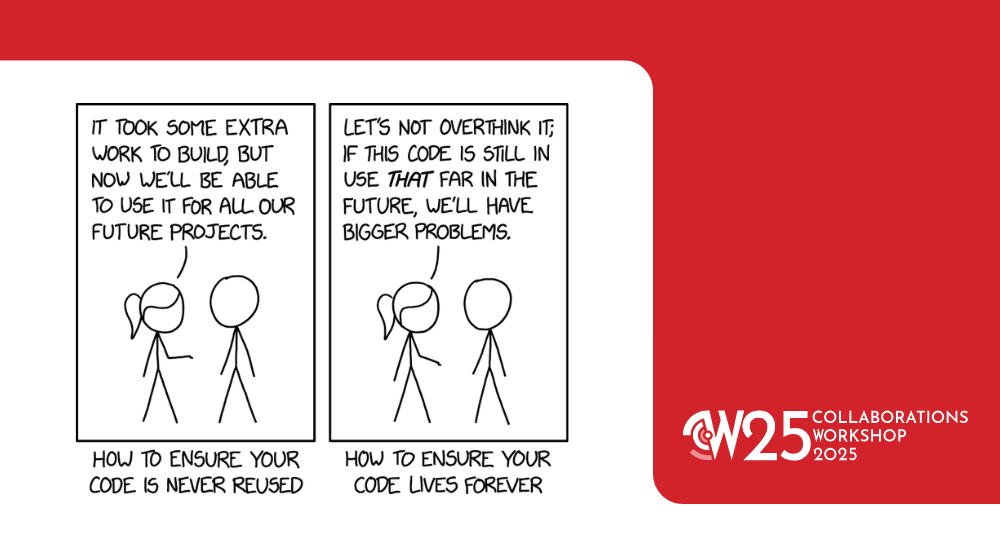

Deskilling: Like GPS navigation that can leave drivers unable to read maps, AI coding assistants risk creating what some call "vibe coding" - development based on feel rather than deep understanding. The experience of becoming dependent on AI - and, as a consequence, losing or never developing skills - varies dramatically across career stages: junior developers may never develop fundamental coding skills, while senior engineers might find some of their hard-won capabilities gradually atrophying through disuse.

Quality, Bias, and Technical Debt: AI-generated code often looks polished but can introduce subtle or even gross errors, create unexplainable logic, and fail in unexpected ways. Debugging these issues can be particularly challenging because AI-generated code may implement logic that seems reasonable on the surface, but does not correspond to the way humans would normally code. Moreover, the "computer always says yes" phenomenon means AI tools rarely push back on requests, even when they should. A tendency toward confirmation bias - where AI consistently follows the user's direction regardless of merit - can obscure when we've taken a wrong turn, making it increasingly difficult to recognise flawed approaches or dead-end paths.

On a more philosophical note, our group also discussed how AI's outputs come with an unexpected cost: they lack the distinctive character that makes human-written code feel approachable and engaging. There's something to be said for code that bears the fingerprints of its creator - quirky variable names, explanatory comments, elegant workarounds that speak to human creativity.

Domain-Specific Risks: The stakes vary dramatically across research domains. In medical research software, AI-generated errors could impact patient safety decisions. In climate modelling, subtle bugs could affect policy recommendations. High-risk domains require especially careful validation of AI-generated code.

Ethical and Legal Concerns: AI training data can include copyrighted code and personal information scraped from the internet without explicit consent, raising both intellectual property and privacy concerns that remain legally murky [2]. Beyond data collection issues, LLMs can perpetuate and amplify societal biases present in their training data, potentially reinforcing stereotypes related to gender, race, or other sensitive attributes (though this is less relevant to discussions about using AI as coding assistants) [1]. The concentration of AI development in big tech companies also means that access to advanced AI capabilities is increasingly controlled by commercial entities whose priorities may not align with research needs - creating dependencies on proprietary systems where pricing, availability, and development directions are determined by market forces rather than scientific priorities. Interests may not align with research values or democratic principles, potentially giving unethical entities influence over scientific computing infrastructure. Additionally, the opacity of these "black box" models makes it difficult to understand how they arrive at outputs, complicating accountability when errors or biased results occur.

Environmental Impact: The computational costs of AI tools raise serious climate concerns, as training and running large language models require enormous energy consumption. Researchers at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst found that training a large AI model can emit more than 313 tons of carbon dioxide equivalent - nearly five times the lifetime emissions of the average American car, including manufacture of the car itself [3] (note that this 2019 study examined models orders of magnitude smaller than current frontier models). These training emissions, while substantial, are dwarfed by deployment at scale: while individual inference queries have much smaller carbon footprints, GPT-4o inference at 700 million daily queries would generate between 138,125 and 163,441 tons of CO2 annually [5]. The energy demands continue every time the model is used (however, see [4]). Models also show striking disparities in carbon footprint - recent benchmarking [33] shows that the most advanced models produce over 70 times more CO2 per query than efficient alternatives.

It is important to contextualise these emissions: data centres currently account for just 0.5% of global CO2 emissions (with AI comprising about 8% of that, or 0.04% of global emissions) [6]. However, the IEA projects data centres will reach 1-1.4% of global emissions by 2030, with AI's share growing to 35-50% of data centre power. As AI usage continues, the cumulative environmental impact could become substantial, raising questions about alignment with climate goals.

But the Benefits Are Transformative

The productivity gains from AI tools, when used skilfully, can be extraordinary. Since systematic research on RSE-specific contexts is lacking, we rely on evidence from industry and general software development - though many of these benefits are likely to transfer to RSE work.

Multiple studies show developers complete tasks 55-56% faster with AI coding assistants like GitHub Copilot [7, 8]. McKinsey research [12] found documenting code takes half the time, writing new code nearly half the time, and refactoring nearly two-thirds the time. A large-scale study [3] found 26% more completed tasks with 13.5% more commits. However, productivity impacts vary significantly by context and developer experience. A 2025 METR randomised controlled trial [16] found experienced open-source developers took 19% longer when using AI tools on their own repositories - despite believing they were 20% faster. Factors included time reviewing AI code, context switching overhead, and misalignment with project-specific standards in mature codebases. This suggests benefits may be greatest for newer developers or unfamiliar technologies, while experienced developers on complex codebases may see smaller gains.

Research shows mixed but generally positive code quality impacts. GitHub studies [10, 11] found 53.2% greater likelihood of passing unit tests and 13.6% fewer readability errors. However, independent studies like GitClear's research [15] have raised concerns about increased code churn and maintainability issues, indicating quality impact varies based on usage context.

Industry reports suggest significant potential for AI in documentation workflows, including generating technical specifications and API documentation [14]. For RSEs, who often work with research codebases that suffer from inadequate or missing documentation - a common issue in academic software development - AI tools could help generate comprehensive README files and inline comments, making these codebases more accessible to new team members and improving overall code maintainability.

While systematic studies specifically focused on RSE contexts are lacking, making it unclear how these general productivity gains translate to the specialised work that RSEs do, anecdotal reports from our discussion group (and more broadly from RSE community members) indicate that AI tools usually help in one or multiple of the following ways:

- Code generation and completion: Writing new code faster, generating boilerplate, autocompletion.

- Learning and knowledge transfer: Helping understand unfamiliar code, languages, APIs, domain knowledge.

- Code analysis and improvement: Analysing existing codebases, suggesting optimizations, finding issues.

- Documentation and communication: Generating docs, comments, explanations

- Debugging and problem solving: Helping trace issues, explain errors.

Learning and knowledge acceleration deserves special treatment - while AI tools risk deskilling through over-dependence, they also offer perhaps one of the most transformative benefits: the ability to dramatically flatten learning curves. The key lies in how they're used - as a crutch that prevents learning, or as an accelerator that enhances it. Crucially, successful AI use depends heavily on one's ability to evaluate AI outputs. If someone has no foundational knowledge in a domain, they will likely struggle to judge whether AI has solved a task well. The fundamental requirement for effective LLM use is being able to verify whether the AI is providing good responses.

AI serves as an always-available collaborator, particularly valuable for RSEs working in isolation or tackling new technologies, both being a common situation. Studies [2, 9, 13] show that newer and less-experienced developers see the highest adoption rates and greatest productivity gains from AI tools, with research across three domains finding that AI tools significantly narrow the gap between worst and best performers.

For RSEs specifically, this learning acceleration is particularly valuable given the breadth of technologies and domains they typically encounter. AI assistance can enable rapid mastery of new programming languages, understanding legacy scientific codebases faster, and getting up to speed on unfamiliar libraries. The weeks or months required to become productive with a new research tool, domain-specific algorithm, or scientific computing framework can be compressed into days.

This is especially significant for early-career RSEs who may feel overwhelmed by the vast landscape of scientific computing, or for experienced RSEs moving into new research domains where the learning curve has traditionally been steep. The ability to quickly understand and work with unfamiliar codebases, APIs, and domain-specific practices removes a major barrier to contributing effectively across diverse research projects.

Keeping Your Job in an AI-Driven World

Fears and concerns about AI are valid, yet choosing not to engage isn't a viable option. Just as GPS revolutionised navigation while creating new dependencies, AI tools are transforming how we write code while introducing new risks. Experienced users can leverage these tools effectively because they understand when to trust them and when to question their outputs. The challenge lies in ensuring that newcomers develop the underlying skills to recognise when they're being "led into a river."

The Threat

The threat of AI displacement is real and already happening. Recent data shows that 14% of workers have already experienced job displacement due to AI or automation [18], with Goldman Sachs estimating that 6-7% of the US workforce [17] could be displaced if AI is widely adopted. A comprehensive PwC survey spanning 44 countries found that 30% of workers globally fear their jobs could be replaced by AI within the next three years [19]. Entry-level positions face particular risk, with estimates suggesting that AI could impact nearly 50 million US jobs in the coming years [20].

Coding is both where AI currently excels most and where it's improving fastest - telling evidence came in 2024, when software developer employment flatlined after years of consistent growth [22]. According to 80000 Hours [21], within five years, AI will likely surpass humans at coding even for complex projects, with developers transitioning into AI system management roles that blend coding knowledge with other capabilities - though this shift will challenge some.

The Opportunity

Understanding AI's limitations helps identify where human skills remain essential. AI struggles with three categories of tasks [21]: those lacking sufficient training data (like robotics control, which has no equivalent to the internet's vast linguistic datasets), messy long-horizon challenges requiring judgment calls without clear answers over years (like building companies, directing novel research, setting organisational strategy), and situations requiring a person-in-the-loop for, e.g., legal liability or high reliability. Moreover, there are valuable complementary skills when deploying AI: spotting problems, understanding model limitations, writing specifications, grasping user needs, designing AI systems with error checking, coordinating people, ensuring cybersecurity as AI integrates throughout the economy and bearing ultimate responsibility. These skills resemble human management: both difficult for AI to master and complementary to its capabilities. As AI improves, they become more needed, multiplying their value.

As stated previously, while coding represents AI's strongest current capability and its most rapid area of improvement, it has simultaneously made learning to code more accessible and expanded what individual researchers can accomplish. This may increase the value of spending months (rather than years) learning coding as a complementary skill, especially if cheaper production costs expand overall software demand.

80000 Hours’ single most important piece of practical advice for navigating AI-related transitions is to learn to deploy AI to solve real problems. As AI capabilities advance, people who can effectively direct these systems become increasingly powerful. For RSEs, starting points might be using cutting-edge AI tools as coding assistants in their current work, and when opportunities arise, building AI-based applications to address real problems.

The RSE Advantage

We believe RSEs may be uniquely positioned to thrive in an AI-driven world. Unlike pure software development, RSE work requires deep domain expertise, understanding of research methodologies, stakeholder communication and management skills, and the ability to translate evolving scientific requirements into robust software solutions.

Importantly, many of the skills where AI struggles align closely with RSE competencies. RSEs routinely navigate messy long-horizon challenges - directing the software implementation of novel research projects, setting technical strategy for evolving scientific requirements, and making judgment calls where clear answers don't exist. Their work inherently requires a person-in-the-loop for research integrity, reproducibility, and ethical compliance. Moreover, RSEs are particularly well-positioned to develop the complementary skills that become increasingly valuable as AI advances: problem-solve in complex research contexts, write specifications that bridge science and software, grasp diverse user needs across research domains, coordinate interdisciplinary teams, and bear ultimate responsibility for research software reliability. These capabilities - to a huge extent involving project and people management in research contexts - are precisely the skills that AI finds most difficult to replicate and that become more valuable as AI handles more routine coding tasks.

RSEs also operate at the cutting edge of research, where problems are often novel and solutions aren't readily available in LLM training datasets. Just as research itself evolves and adapts, RSEs can leverage their research background to stay ahead of automation. It's precisely in these uncharted territories - where science meets software - that AI tools may remain limited and human insight becomes indispensable.

Essential Skills for the AI Era

- Prompt Engineering: Learning to communicate effectively with AI tools, including crafting prompts that encourage critical evaluation rather than blind compliance.

- AI Literacy: Understanding AI capabilities and limitations, knowing when to use different tools and when tasks can/can not be delegated to an AI agent, and recognising the environmental and ethical implications of various choices.

- Enhanced Validation Practices: AI-generated code may require especially careful validation since errors may not be immediately obvious to human reviewers. Using and extending already existing best development practices, as well as the ability to judge when AI suggestions are leading in the wrong direction, will be crucial.

- Continuous Learning: As AI capabilities evolve rapidly, staying current with both benefits and risks requires ongoing professional development.

Community Actions and Recommendations

The research software community can navigate this transition successfully via:

Training and Education

- Establish foundational AI literacy programs: Help RSEs understand AI capabilities, limitations, and appropriate use cases across different research domains.

- Develop adaptive learning frameworks: Since AI models evolve rapidly and best practices are still emerging, create flexible training approaches that can evolve with the technology rather than rigid curricula that quickly become outdated.

- Foster critical evaluation skills: Train RSEs to assess when AI assistance is helpful versus harmful, and how to validate AI-generated outputs effectively.

Standards and Guidelines

- Develop protocols for disclosing AI assistance in code development and research publications.

- Create environmental impact metrics for AI usage (tools like CodeCarbon can help track computational costs).

- Establish quality standards and validation procedures for AI-generated code in research contexts.

Available Tools and Technologies

The research software community has access to a growing ecosystem of AI tools, each with different strengths:

- Conversational AI Models: ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, and open-source alternatives like Mistral and DeepSeek offer different capabilities for code generation and problem-solving.

- Integrated Development Tools: CursorAI, GitHub Copilot, and Windsurf provide AI assistance directly within coding environments, while tools like Claude Code, OpenCode and OpenAI's Codex agent enable autonomous coding through various interfaces including command line.

- Local and Specialised Tools: Ollama allows running models locally for sensitive research, while tools like LangChain facilitate building custom AI applications. OpenCode provides terminal-based AI assistance with support for 75+ LLM providers.

- Cloud-Based Autonomous Agents: OpenAI's Codex and Claude Code offer cloud-based software engineering with parallel task execution, while platforms like Manus provide more general-purpose autonomous assistance that can handle coding, among other complex tasks.

The variety of available tools means RSEs can choose solutions that match their security requirements, domain needs, and workflow preferences. Moreover, experienced developers have moved beyond simple chat-based interactions to develop structured workflows for AI-assisted development. Mitchell Hashimoto, for instance, proposes to iteratively build non-trivial features through multiple focused AI sessions, each tackling specific aspects while maintaining human oversight for critical decisions [23]. Geoffrey Litt advocates for a 'surgical' approach where AI handles secondary tasks like documentation and bug fixes asynchronously, freeing developers to focus on core design problems [24]. Peter Steinberger takes this further with parallel AI agents working on different aspects of a codebase simultaneously, using atomic commits and careful prompt engineering to maintain code quality [25]. These workflows share common principles: breaking work into manageable chunks, maintaining clear documentation for AI context, and crucially, always reviewing AI-generated code before deployment.

Conclusion: Looking Forward - Integration, Not Replacement

The expertise in leveraging AI dev tools is being developed primarily in industry, creating a risk that RSEs may fall behind in AI proficiency compared to their industry counterparts. Rather than rejecting AI tools outright, RSEs could position themselves at the forefront of AI usage knowledge, leveraging it to their advantage while actively addressing the legitimate concerns and working to mitigate the risks we've outlined - from deskilling and environmental impact to ethical considerations and quality assurance.

The RSEs who thrive will be those who learn to use AI tools effectively while maintaining the critical thinking, domain expertise, and ethical considerations that define excellent research software. They understand that their value lies not just in writing code, but in asking the right questions, understanding research contexts, and ensuring that software serves scientific discovery. We still need skilled developers who can recognise when they're being led astray.

As we navigate this transition, the research software community can work together to ensure AI enhances rather than replaces the human elements that make RSE work valuable. The question isn't whether AI will change our field (it will and already does) - it's whether we'll shape that change to serve research and society's best interests.

Want to join the conversation? The research software community continues to explore these questions through workshops, training programs, and collaborative initiatives. Visit software.ac.uk to learn more about upcoming events and resources.